Could Students be Motivated to Learn without Grades?

Students are motivated to dive into research when they the relevancy to their lives.

October 25, 2019

For as long as any of us can remember, the idea of getting good grades has been ingrained in our minds. Some students may attain such grades easily while others struggle with reaching the same level. But should there be more motivating students to comprehend than grades? Such discussions over grades has even sparked a national debate, such as this article from Edutopia about whether schools in America should keep grades as a system to measure learning.

In most situations, in order to attain success, incentives are placed to get the desired results. Say the incentive is free Chick-fil-a and Honor Roll in exchange for getting good grades all quarter. Hearing these promises would boost the students desire to get good grades because they get something out of it. Or even some students are motivated just getting an A to feel accomplished. The real question is, what happens when the use of bribes and rewards are the only motivation?

Here at Kenwood, the problem doesn’t seem to be the students desire to learn. In fact, at times it could be quite the opposite. Some students are motivated by the material they’re learning. For instance, senior Zamir A. said, “I love learning something new, always. I find school a lot of fun, one: because of the social aspect but also because I like certain classes.”

But one experience doesn’t speak for all when it comes to motivation for learning. Some may say it depends on what they’re learning. One English teacher, Dr. Lobo says, “I think it depends on how you define learning, and how you define the process of learning.” Another teacher, Mr. McWhorter states that he believes all students are interested in learning, but it depends on the topic of the day and how relevant it is to their life. But with all these extra factors, the main culprit seems to be about relevancy as a whole. If students find the material relevant it has the potential to motivate them as much as grades or other rewards.

The issue at hand is more on the line of relevancy to everyday life and students seeing the need for what they are learning. Kenwood Principal Mr. Powell says, “We want to be sure we provide the purpose for our students. The goal is to plan engaging activities for students to both want to be able to learn information, but more importantly start to apply it to the goals that they have set for themselves.” In other words, “the more we make those things relevant to our students, the more that we can impact the learning that’s taking place in the building.”

It is no surprise that the idea of relevancy is a huge factor for motivating students to learn. Almost everyday you have a high possibility of hearing a student say, “When am I going to use this after school?” Which, to be fair, is completely understandable. Unless you’re going into a specific field that’s related to something like statistics for example, to the average student taking the class could seem pointless. This viewpoint goes back to the idea of students being unmotivated because of irrelevancy and the desire for good grades or awards functions as their only motivator. If we make the subjects more relevant to the lives of our students, or even take away incentives like grades and awards, would the student body be self-motivated to learn for their own good? Or would they even care to continue with school?

Even as education moves towards attempting to make classes as relevant as possible, will it be enough to motivate even the most reluctant of students? Put it shortly, no. There are more factors to student motivation than just relevancy. Whether it’s home problems, simply not feeling well, even stress from other classes, or just having a bad day or year some students show up to class completely unmotivated. Is it even possible for any of us-students or adults to give our all ALL of the time? But whatever the outside factors may be influencing a student’s motivation students and teachers sometimes feel penalized for the students that aren’t self-motivated or even interested in education in general.

Senior Myasiah B shares, “You have some students who are driven by grades to learn and can be self-motivated, and then you have ones who are like ‘I’m just going to do what I need to to get by.’ ”

Yet the question still comes up again: Is doing something just to get by a good thing? Zamir says that awarding students with titles and awards such as Honor Roll can teach people that they should only do things when they are rewarded. Without seeing the reward or getting instant gratification, which is now seen as the norm, doing day-to-day classroom tasks can take a lot of effort from the most unmotivated student that seems pointless to them in the moment.

The solution to student motivation isn’t very clear; however, making sure that all students see a relevancy to their education is becoming an education priority. Without some personal gain or relevancy tying students to school, some may not see a reason in even attending. Myasiah added, “Despite classes I don’t really like, I know I need to be there to get my diploma and anything that I do in life is going to require me to have a diploma. I know it’s a must if I’m going to apply for college or go to nursing school.”

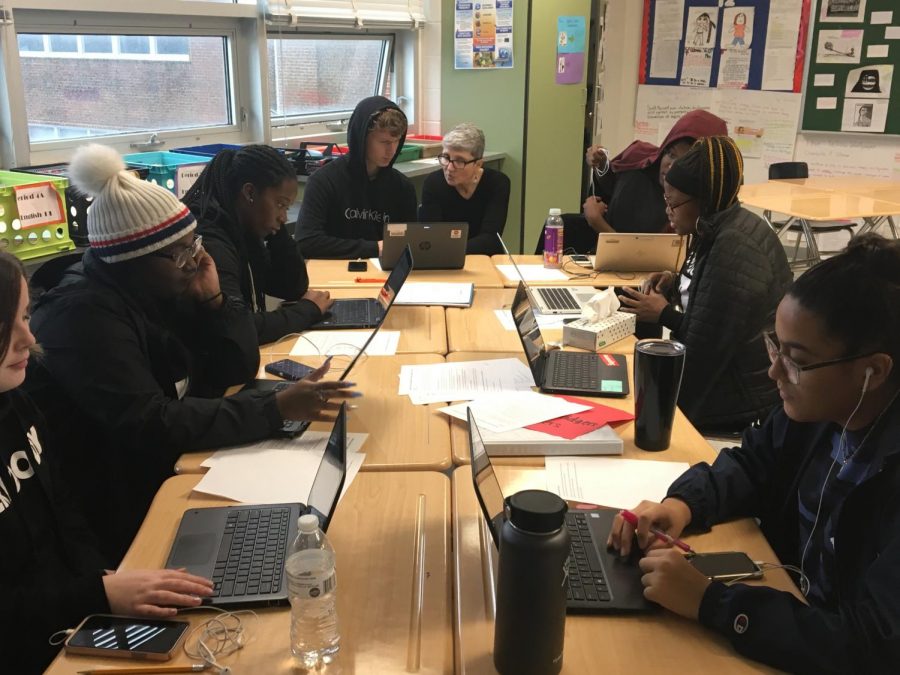

Some teachers, like Mr. McWhorter and Dr. Lobo have taken the initiative to make sure students are more engaged in lessons. For example, Dr. Lobo assigns students to write about their favorite musicians to get students engaged in writing. In McWhorter’s classes he tries to make sure there is a variety in daily assignments and getting students moving so they’re not sitting in seats all day. “In many of my classes I try to vary the lessons by using groups and with visual learners. Sometimes we’ll do hands-on things; some days we’re reading and writing, but we’re not doing that the entire period.” When students see that their teachers are passionate about what they’re doing, it also helps motivate students to care about what they’re learning, too. If the teachers themselves are just teaching as a job without passion, why should the students care to do the work?

It is a give and take when it comes to the issue of student motivation. If eliminating grades is in the future of education, students must see a relevant purpose for what they’re doing if they’re going to succeed in school. Acknowledging the issue of relevancy and its role in student motivation is a step towards trying to solving the problem of student motivation.

thomas williams • Dec 17, 2019 at 12:33 pm

I read with great interest this article concerning grades, and about making lessons relevant to students in order to help them succeed in class and get good grades.

Students should forget about grades. They should enroll in the most challenging classes they can, struggle all they can and not worry about failure. Failure is how we grow. Struggling is how we grow.

The purpose of education is to create deep thinkers, not lots of high scoring students who know little about the world they live in and their place in it.

I think of Bill Murray in the film Tootsie. He is a playwright, and he is asked about how he wants the audience to respond to his plays. He says, “I don’t want people rushing up to me after a performance telling me how great it was. I want them coming up to me a week later asking me ‘what was that about?’”

Students should come out of classes, like Bill Murray’s theater goers, asking the question “what was that about?”, and feel responsible to find the answer that question.

It is the struggle that matters, not the documented result of that struggle.

I have recently taken to giving my philosophy students readings that are difficult to understand and with no purpose for reading them. You tell me: what it means. You tell me why it is relevant. This goes against the current tend of stating an objective and seeking to reach it through lessons that are designed to meet students where they are, thus “relevant”.

But it is delighting me because its making me feel like a real teacher, helping students to struggle and make sense of ideas that are beyond their immediate grasp.

This is what I put myself through in college. I took very difficult courses, reading books I could scarcely understand and got lousy grades. In search of their meaning, I continued to read those books after the classes were over, and I still don’t understand some of them, but that’s okay. The struggle continues, as it should.

But here is the secret I shared with my students struggling with these readings: once one “gets it”, it can lead to an awakening that give one a feeling of not just pleasure and joy that is unmatched in thus world. It gives one a feeling of being in control, of meeting a difficult challenge with the most profound relevancy of all: it allows one’s mind to grow. And once a student realizes this, there is no more search for relevancy. It is baked in us. Once one tastes the pure joy of becoming aware, of growing, the search for more never stops.

There should be no need for a teacher to ‘make relevant’ the readings of Beuwolf, of Machiavelli’s The Prince or anything else taught in school. The purpose of education is to give students the opportunity to explore and find the relevance for themselves. We should be guiding them. If we are not doing that, we are shortchanging the students.

As far as grades go – well, for one thing, it’s just too easy to cheat to get good grades. It’s too easy to get good grades from teachers who find themselves, due to being overwhelmed by the body of student work to grade and increasing administrative demands, at least some if the time, grading for completion.

Thus, students prefer the challenge to getting good grades than they do the challenge of engaging and making sense (relevancy) of the material. Who can blame them? It’s easier.

Why does a student need good grades? To get into a good college? What good does it do to get into a good college if one has not been prepared for the intellectual struggle to come? How much debt will this student going to a good college be burdened with?

A student who has struggled and learned, but finished with mediocre grades can go to a community college and thrive. And afterwards, use those good community college grades to get into and finish their college education at a quote-unquote good school. The student will be better prepared and face less debt.

So teachers: throw away those objectives, throw away those “relevant” lesson plans, throw away differentiation. Challenge students to tell you what the point is and why it is relevant. Work towards the day a student comes up to you a week later and asks “what was that lesson about?”